Saddle Fitting: More than 9 Points to Perfection

Articles on saddle-fitting are somewhat frequently published in horse magazines, both in print, or online. The articles are usually combined with a bulleted checklist (9-points, 11-points, and so on) to see if your saddle fits. However, the most important ingredient to a successful riding recipe is that the rider understands WHY the saddle should fit that way, and what often happens if it doesn’t fit correctly. This is especially critical as we head into show season and need to recondition our horses after a winter of perhaps less intense training than usual.

I was recently at a tack shop and overheard the ladies next to me trying to find a new saddle. The first woman sat in quite a few expensive models until she found one that was comfortable for her, and the friend helping her looked it over and proclaimed that the tree should fit the horse just fine, “after all, it’s a medium-wide.” No longer able to contain myself, I asked what kind of horse they were trying to fit, and had they thought about at least doing tracings to bring to the store before making such an expensive purchase. These were kind people that only wanted the best for their horse in their new riding adventure, but buying a saddle before fitting it properly to the horse is like buying a bikini for your friend without taking her to the store to try it on! (Worse actually, because buying a bikini that doesn’t fit won’t do you any damage – at least not physiologically speaking!)

Understanding some basic equine anatomy goes a long way in understanding why the saddle must fit correctly for your horse to perform pain free and maximally. The horse’s shoulder must be allowed a complete range of motion to extend the trot, cut cows, or jump fences. The scapula, or shoulder blade, is actually topped with cartilage. A saddle that pinches in this area can actually shear off the delicate cartilage that allows the shoulder blade to glide beneath the muscles that overlay it. The effects of pinching saddles are now documented with advanced imaging, such as MRI and CT scan. There should be some space at the top of the panel to allow for proper range of motion of the scapula.

The saddle tree is designed to provide a frame for the saddle itself, but also to provide support for the curvatures of the rider’s spine, and an interface for horse and rider to communicate. Store-stocked saddles are often marked with different tree widths (narrow, medium, wide, extra wide, combinations of these) but did you know that saddle trees also have an angle? The angle of the tree corresponds to the angles of the shoulders, and the width of the tree correlates to the width of the shoulder muscle. Two saddles may be labeled as “wide tree” but have two completely different angles! You may have a horse with high withers who needs a narrow angle to clear the top of the withers, but a very wide tree to clear the width of the shoulder blades and muscles. Differences in individual anatomy are why fitting a saddle to the horse is so important! One size does not fit all, but we have been taught this way, and manufacturers are able to mass produce their saddles under these categories.

Some signs that your horse may have saddle-fit problems, and secondary back pain:

- White hairs under saddle area

- Bites or acts out when saddled or girthed

- Anxious when mounted, won’t stand still

- Bucks/kicks under saddle

- Bolts

- Chips or rushes jumps

- Trouble with leads/lead changes

- Improper muscle development – no topline

- Stiff to warm up/cold-backed

- Trouble with collection or lateral work

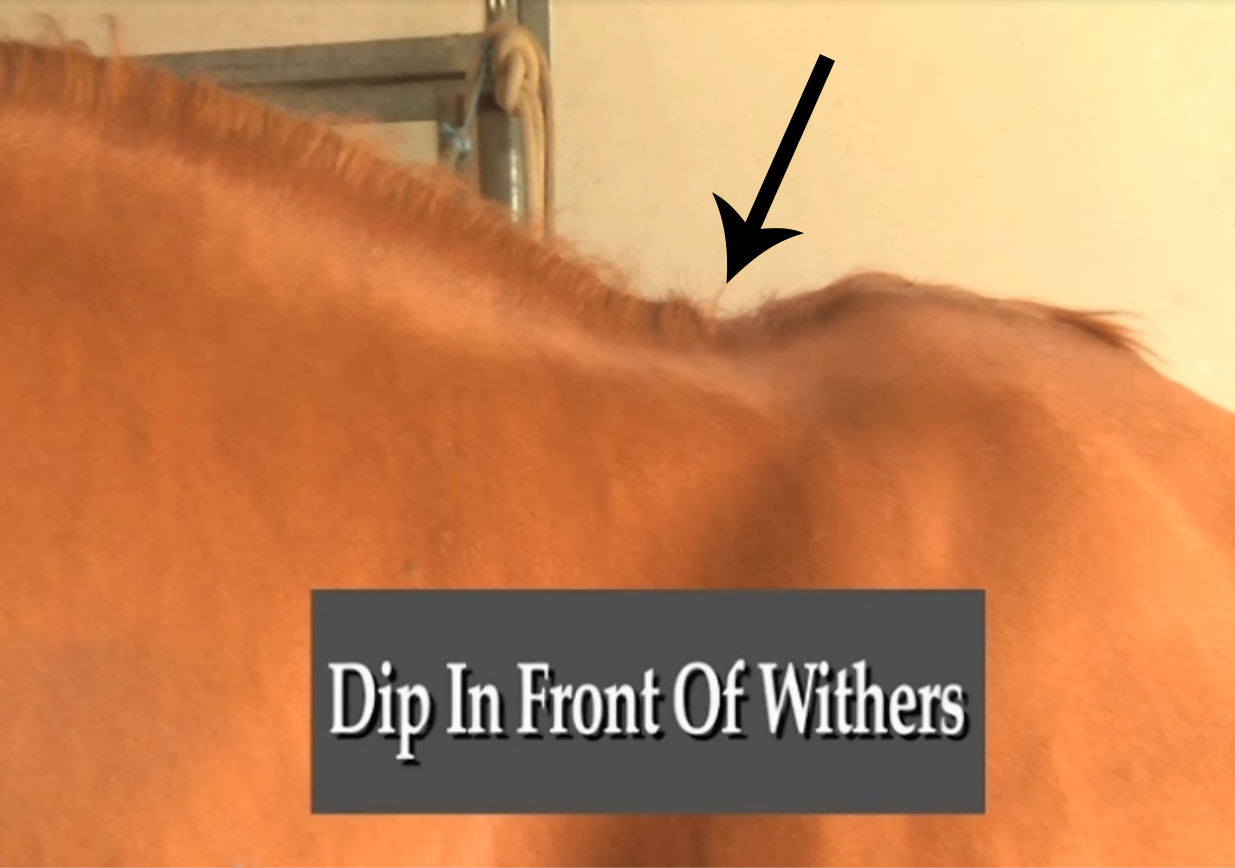

There is a thin muscle called the trapezius that originates on the spine of the shoulder blade (you can feel this on your horse with your index finger) and extends forward up the neck, and back behind the withers. The function of this muscle is to elevate the scapula and hold it to the body wall. Horses that are trying to pull their shoulders down and away from a pinching saddle may often have atrophy in this area. Look around, and you will see horses that have a visible dip in front of their withers.

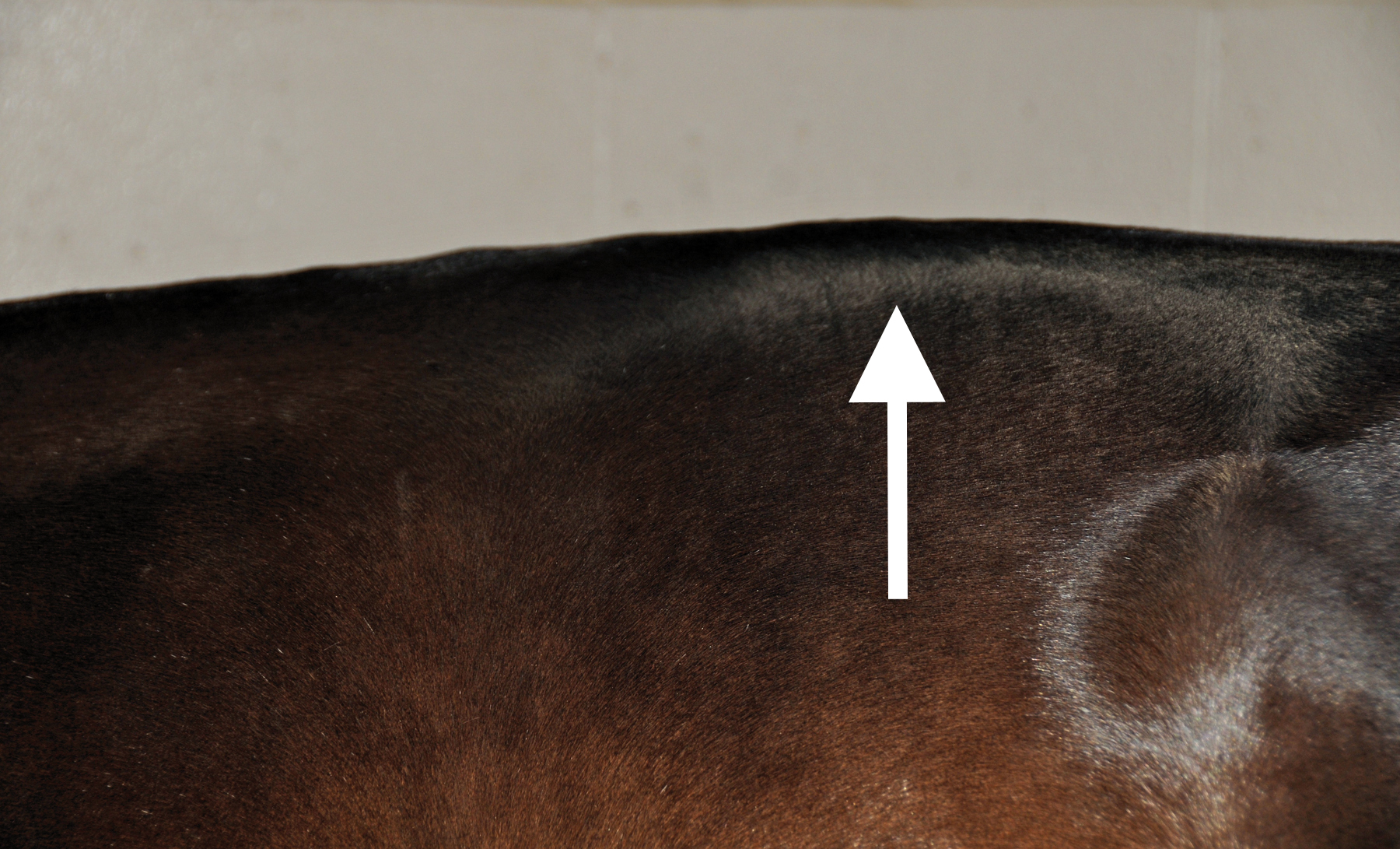

Next, there is a nerve that exits directly from this trapezius muscle behind the withers. This nerve is cranial nerve (CN) 11, also called the Accessory Nerve. Poke or squeeze your horse in the shaded area a few times and witness his reaction. His head comes up, his back dips, his tail swishes, his muscle twitches, and he may even turn to bite you. Now imagine you have a saddle that crushes this area every time you ride. Does your horse pin his ears or get upset when you approach him in the crossties with your saddle? He’s trying to tell you that he hurts. Some horses with chronic shoulder pinch will also develop a more obvious line across the shoulder. This line is where the cutaneous trunci muscle will flicker if a fly lands on your horse. When you pinched behind the shoulder, did you notice the muscle flicker? With constant stimulation, a distinct line or groove may become visible.

The channel of the saddle should be wide enough that it doesn’t rest on the transverse processes of the vertebrae, or on the paraspinal ligaments. Pressure here can cause fluid buildup in the tissues, much like a water blister, although the fluid has nowhere to exit. This rubbing is also equivalent to you wearing a pair of shoes that fits too tightly. You know that rub sore you get on the back of your ankle? A tight saddle does the same to your horse. A saddle should have at least 3 fingers’ channel clearance all the way from front to back, and in the case of today’s big warmbloods or broad Quarter horses, most horses need 5-6 fingers’ width.

Though Western saddles are often much wider through the channel, their fault is that they are frequently too long. Their excessive length, and frequently hard skirt leather puts undue pressure on the horse’s lumbar spine and croup. And the added weight of these saddles maximizes their pinching effect if they don’t fit correctly through the shoulders. An English saddle should not extend past the 18th vertebrae. Horses have 18 ribs, so you can trace the last rib to the spine to find your rear border.

A common error is to place your saddle too far forward! Even a saddle that doesn’t fit perfectly is a little better placed behind the shoulders where it belongs. Place the saddle up on the withers, then slide it back into position until it “locks into place.” Look to see if there is enough room at the top of the saddle to allow the shoulder-blade to rotate backwards without bumping into the tree. And remember, a saddle that fits only needs a thin wither-relief/contoured pad. Saddle pads for saddles that don’t fit are only a band-aid. They merely change the pressure points temporarily, until new areas become sore. Remember, if your shoes are too tight, wearing thicker socks won’t fix the blisters!

Finally, there’s no better way to ensure proper saddle fit than to have your horse with you when trying saddles, and to enlist the help of a certified professional to help you. Ensure that the individual is a veterinarian or a certified saddle fitter, and not just a sales representative from a company. If you cannot take your horse with you, making simple tracings are worth the effort. Some tack stores will also allow saddles to be taken on trial for a deposit. Horses’ bodies change over time, just as ours do. You don’t wear the same pair of jeans you wore as a 6 year-old, so don’t expect that a non-adjustable wood or plastic treed saddle will fit you and your horse the rest of your lives. Advances are being made in adjustable gullets and adaptable trees, but both the angle and the tree width must be taken into account. Treeless saddles are also finding popularity, but have their own issues. Armed with education and determination you can find something comfortable for you and pain-free for your horse, and have enjoyment for years to come.

©2016 Saddlefit 4 Life® All Rights Reserved