Saddle Fit and ‘Bad Behaviour’ – Part II – Cranial Nerve 11 (CN11)

Cranial Nerve 11 (CN11)

While this may seem like a rather dry conclusion to the little series on “Horses Behaving Poorly” it actually explains a lot.

Over 50 million years of equine evolution have seen the stallion biting its opponents in the wither area to determine dominance and literally bring rivals ‘to their knees’. Stallions will also bite mares in the exact same area in preparation for mating – to stop them from moving forward and to be able to mount them safely. Predators will also attack in this same region of the neck to hinder the flight response and to bring the prey down.

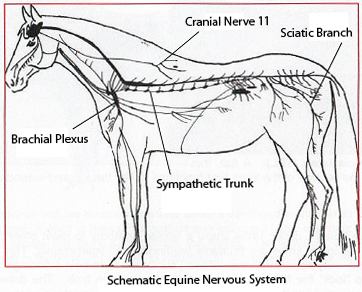

This reflex point is known as Cranial Nerve 11 (CN11). Pinching gullet plates, lungeing girths, vaulting girths, driving harnesses and foregirths will achieve the same result as the stallion’s bite acting upon the muscles in the wither region like a vise grip. Nature has determined three survival mechanism reflexes for CN11: if the mare or the rival horse is bitten here, or if the gullet plate of the saddle pinches the side of the withers here, the nerve signals to the brain that the movement in the upper arm and shoulder blade be blocked. The second signal ensures that the longissimus muscle contracts, dropping the horse’s back (and that the vertebrae fall into each other as in kissing spine syndrome). Thirdly, the pelvis will rotate forward and open as a result of further contraction of the longissimus, opening the area in preparation for mating.

All three of these reactions will result in reflexive immobility for the horse. In nature they are critical for survival; allowing the stallion to mount the mare without being kicked, and ensuring that the rival is immobilized during a fight for dominance.

The paradox is that we as riders want to achieve exactly the opposite! We want a horse with a loose, supple and engaged back and the ability to ‘step under’ with the hind end. Only in this way will we ensure that we are not riding on the forehand, to take pressure off all the ligaments, tendons, muscles, and bones of the horse to keep it healthy for a full lifetime of enjoyment and riding in harmony. This is achieved only if we ensure that there is no pressure on this cranial nerve 11 from a gullet plate that doesn’t fit.

Bucking Reflex

This reflex point is located over the fascia behind the 18th thoracic vertebra. The horse’s first reaction is to try and get rid of pressure from a saddle that is too long, pressing on the fascia in this area over the transverse processes. Further indications of a saddle which is too long are doing a pace during the walk (both front and hind legs on one side move together rather than diagonally with the opposite side), dragging the hind legs during the trot, or showing a four-beat canter.

“Girthiness”

“Girthiness”

When using a short girth, watch that the buckles do not press on the edge of the pectoral muscles. For a long girth, attention must be paid to the same issue, but at the edge of the latissimus. The buckles can cause concentrated pressure points in these areas, which cause the muscle fibres of the triceps to contract to try and avoid this pressure and the resulting potential rub marks (instinctive self-protection measure). The rider will have difficulty finding a good extension in the trot and will experience poor transitions between the gaits. The pectoral muscles need full range of contraction and relaxation to allow huge and natural extension; only with complete freedom will the biomechanics work, as they should.

If either the panel points or the billets exert pressure on the subscapular and thoracodorsal nerves, the natural reflex from both or either of these nerves will also cause the triceps to contract, inhibiting movement in the front. The horse moves like a ‘sewing machine’ (on the spot, more or less) and tripping or stumbling can also result.

This comic really exemplifies (tongue in cheek) the whole concept of ‘bad behaviour’. Used with permission Jean Abernethy.