Saddle Fit and Panels – Gullet Width and Full Panel Contact – Tips 3 and 4

Continuing on with the detailed discussion on each of the nine points of saddle fit – this week we will examine specifically that part of the saddle which is closest to your horse – the panel.

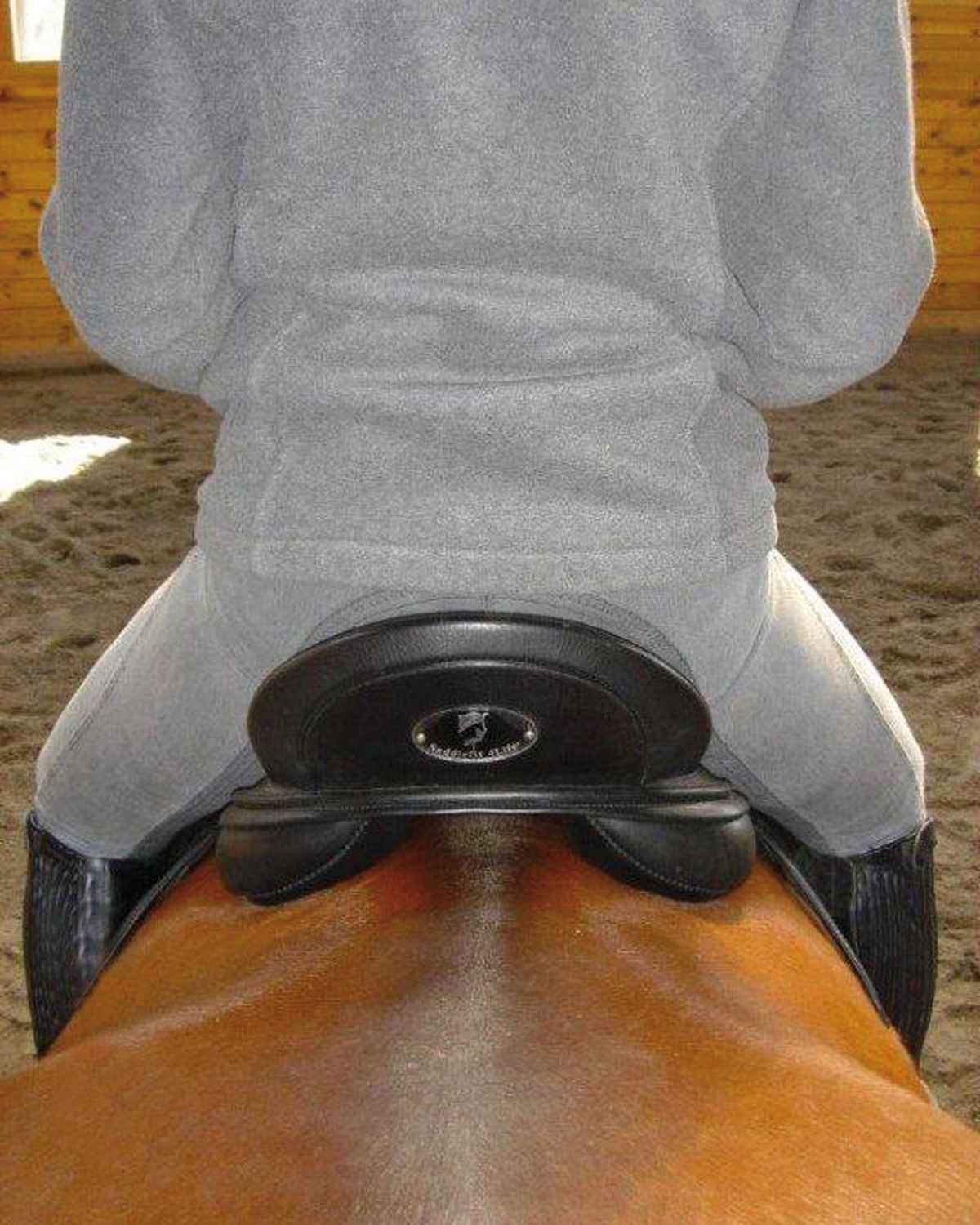

Panel Gullet Width

I have had many clients with saddles that at first glance look like they’re fitting really well, but when I turn them over, I see that the gullet width is awfully narrow – maybe 1-2 fingers! A saddle with a channel or gullet that is too narrow can cause permanent damage to your horse’s back (but also, if it’s too wide that’s not great either!) I will tell you how to determine if your saddle’s gullet is the correct width for your horse.

There is no such thing as “one size fits all” where the channel or gullet of your horse’s saddle is concerned. Instead, the width of each horse’s spine will determine how wide his saddle’s gullet must be.

To calculate how wide your horse’s spine is, do the following: Stand on your horse’s left side and place your hands on his spine in the area where his saddle will sit. Then, with the tips of your fingers, gently palpate downward towards the ground. You will first feel bone (the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae), then a slight rigidity (the supraspinal ligament), and finally, an area where there is a bit more give. This is his back muscle or longissimus dorsi muscle. Mark the start of this muscle and then do the same thing on your horse’s right side. Next, take your right hand and make a bridge over your horse’s back from mark to mark. Put your left hand inside that “bridge.” The number of fingers you can get inside your bridged hand will determine how wide the gullet of this horse’s saddle must be.

It is very important that the width of the gullet be the same throughout the entire length of the saddle. Too often we see saddles with gullets that are the appropriate width at the front, but then get progressively narrow towards the back. The result is a saddle that has a 4-5 finger gullet under the pommel, but only 2-3 fingers at the cantle (or less). If you consider the anatomical structure of the horse’s back, this makes no sense. The horse’s spine and surrounding ligaments do not get narrower over the length of his saddle-support area. In order to ensure adequate spinal clearance all the way down, neither should the gullet of his saddle.

It is only infrequently that we find a saddle that is too wide through the gullet for a particular horse. But such a saddle will have inadequate weight-bearing surface, may start to strip muscle away from the top of the ribs, and the back of the tree may actually rest on the spine.

A much more common problem is the saddle with too narrow a gullet. This saddle will sit on the horse’s spine and/or ligaments. This is especially noticeable when the horse goes around a corner: if the horse is tracking to the left, you will see the saddle shift to the right, so that the left-side panel rests on the horse’s spine/ligaments. This is something we must avoid at all costs. In the short-term, a saddle that sits on the horse’s spine/ligaments will cause him to tighten his back muscles and hollow his back, producing exactly the opposite of the nice rounded back that we want to see, particularly in dressage. In the long-term, a saddle with too narrow a gullet will cause permanent, irreversible, and often career-ending injury or damage to the horse’s back. The most severe forms of such damage are spinal stenosis (compression and narrowing of the spinal canal) and spondylosis (degeneration of the vertebrae). I know you will not want to cause your horse such pain!

Understanding the importance of Full Panel Contact.

Full Panel Contact

Once you’ve established that your saddle’s gullet/channel is the correct width for your horse, you need to ensure that your saddle’s panels make even contact with your horse’s back. We want the saddle to sit on the optimal weight-bearing surface of the horse’s back, and to distribute the rider’s weight over an area that equals approximately 220 square inches and ends at the last rib or 18th thoracic vertebra.

How to Check for Full Panel Contact

Put your saddle on the horse without a pad, put your right hand under the stirrup bar area, gently hold the saddle in position with your left hand, and with your right hand palm facing up slowly move your hand from front to back. Put your hand flat on the horse’s back (you have greater sensitivity on the top of your hand), and feel if there is nice even panel contact from front to back. Check this on both sides. If the saddle sits flush at the front and back but only loosely or with no contact in the middle, this will result in excess pressure at the front and back (bridging). If the saddle is tight in the middle and loose in the front and back (rocking) there will be excess pressure in the middle of the saddle. The rider’s entire weight is concentrated in this one area.

Note that sometimes your saddle may be made with panels that deliberately flare up at the very back, so the last inch or so of the panels don’t make contact with your horse’s back. This is done in specialized cases: for instance, when there is a need to accommodate a tall or large rider on a horse with a short saddle-support area. If fitted correctly, this saddle will not rock (although people may assume by its appearance that it will). This extra room is also important for the back to come up when the horse engages during movement.

Sometimes we hear that a saddle that bridges slightly is actually a good thing, because when the horse lifts his back as he is being ridden, his back will come up into and fill in this space. While this may seem logical at first, in reality, it doesn’t work. Scratch your horse’s stomach along his midline, so that he raises his back. You will see that the middle still does not make contact with your horse’s back.

The goal of saddle fitting is to have the saddle distribute the riders’ weight evenly over the saddle support area, and it is important that the saddle neither bridge nor rock.

In a future blog I will discuss panels in more detail, especially the various types of fill used.

©2016 Saddlefit 4 Life® All Rights Reserved